MULTIHULL PERFORMANCE FACTORS

We've put together some information about the factors that determine the performance of multihull yachts and some of the ways that performance can be measured and predicted.

And we propose a more credible method for yacht manufacturers to promote the performance potential of their products.

How fast does it go and can we see your polars please?

We all know about the bar talk and some of the wild claims that are made about boat performance.

I remember one of the crew of APC Mad Max after a particularly windy regatta at Wangi telling me about the after event bar talk.

Some of the crews were talking boat speeds that were a few knots faster than the highest speed the crew of Mad Max ever saw on the GPS .

And yet Max had cleanly taken line honours in every race of the series and was never overtaken on the course.

How do you know how fast boats really are, and are the polar diagrams we see published in boat magazines, on web sites and brochures a credible means to determine performance potential?

POLARS AND SCHMOLARS

There are two methods to generate the data to create polar diagrams.

1. Mathematical modelling with data from resistance curves and known sail force data.

This is complex and highly technical. It is most commonly used for refining rating rules or for design optimisation in high end race boats. But even this level of technology relies on human input

for verification - data from real world observations on the water as in 2.

2. Data compiled from onboard observations. It might be recorded while sailing and downloaded from GPS data after the sailing session.

To do this accurately and methodically over a range of wind conditions, the full spectrum of sailing angles, and a range of sail combinations is a huge undertaking.

This is generally only done by top level racing teams with commercial sponsorship.

A polar diagram for a production boat is unlikely to have been generated from methodically accumulated real world results or accurate mathematical modelling that is applicable to that type of boat.

There may be some exceptions but these polars should generally be regarded more as a marketing tool than accurate performance indicator unless there is some way to verify the results.

If it was the motor industry there would be a gentleman in a white coat with a clip board checking on your claims. In the marine industry there is no such scrutiny and there are no consequences for publishing data that cannot be verified.

So how to judge performance?

Real world performance data

1. Electronic Surveillance

With the level of navigation and tracking technology we have available now it is not so easy to bullshit about your boat speed.

The plots enclosed above record the track and speed of the F33SRX trimaran Carbon Credit. The plots were posted by LowGroove on a Sailing Anarchy forum after Wangi Week in 2014.

They show typical speeds over the course for a fairly high performance trailerable trimaran in fresh wind conditions.

2. Go and get Rated

Race Results and Ratings

The OMR Rule that we race under in Australia and in Thailand has proven to be a very fair and effective measure of multihull performance across a broad range of boat types and configurations.

It will never be perfect because multihull performance prediction is a complicated beast. See also my article “What Makes Trimarans Fast?" which explains some of the complications.

There are numerous variables to deal with and design technology is an ever moving target.

Over the years the administrators of the OMR have done a magnificent job of keeping it up to date and relevant to the extent that you can race a large cruising cat against a very fast small trimaran in a range of conditions and still have a great race.

One shortcoming in the OMR is that the spreadsheet is a bit awkward to use, but it is freely available online and if you know the weight and basic dimensions of your boat including the rig and sail measurements, then you can input your own data and see how your rating stacks up against other boats of similar size and type.

Weight is critical to the rating and all of the boats with a valid OMR rating have been officially weighed.

As a general guide a rating above one is pretty quick. With a rating under about .9 you’re pretty much a cruiser.

You can download the OMR spreadsheet here:

http://www.mycq.org.au/index.php/racing/omr-ratings

3. Look at some fundamental ratios

3. Understand the principles that determine performance.

The two big ones are the power to weight ratio and the displacement to length ratio.

(i) Power to Weight ratio (or sail area to displacement ratio)

Light boats are more easily driven than heavy ones and more sail gives you more drive. This ratio on it's own is the elephant of multihull performance.

Measure the ratio in kg of boat weight per sq.m. of sail area.

C Class cats carry (or have to push) about 8.3 kg/sq.m. A cruising cat might have to carry 120kg/sq.m.

Note that some people used to use the Bruce Number to calculate power to weight. It is unnecessarily complicated and uses imperial measurements. It needs to be buried.

(ii) Displacement to Length Ratio

The displacement to length ratio indicates how easily a hull is driven. A long light hull has less resistance and so will go faster for a a given sail area.

As a bonus the longer hull will have better seakeeping properties, particularly less pitching.

If you’re comparing two boats of the same length you don’t need to use this formula, you already know that the lighter one will be faster if all other things are equal.

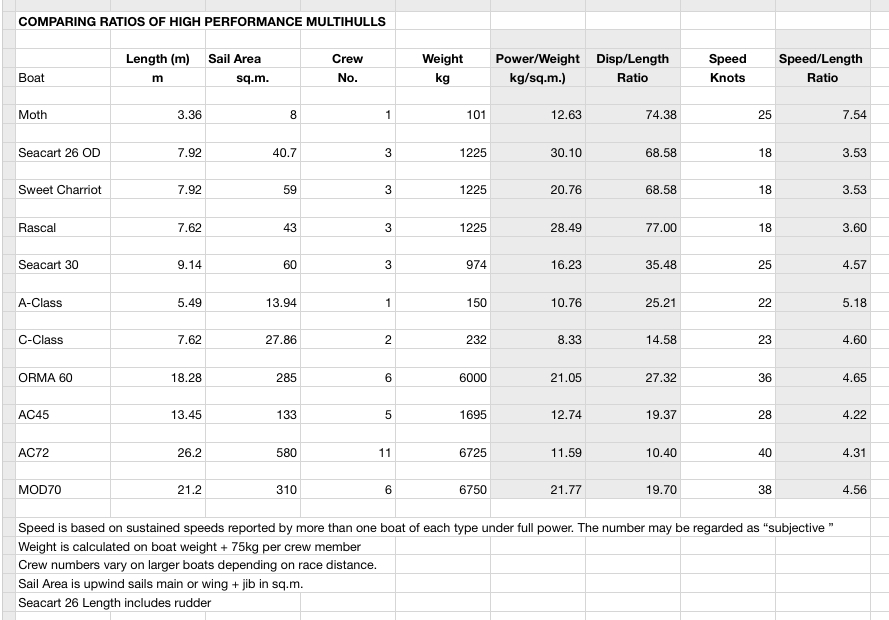

This table shows some typical performance data and design ratios for a selection of high performance multihulls and one moth.