WHY HULL SHAPES MATTER

START AT THE BEGINNING

There are two fundaments we have to address to before we can have a rational discussion about hull forms and they are all too often overlooke in the debate.

We need to establish the weight we expect for the vessel and the centre of gravity of the vessel in sailing trim. If we can't establish those two facts we are flying blind with the hull form. The weight tells us the volume of hull we need to put below the datum waterline, or the designed waterline (they're the same thing). The location of the centre of gravity tells us where that volume must be centered. We call that the longitudinal centre of buoyancy and unless it lines up in the vertical plane with the centre of gravity of the vessel then our boat is not going to trim correctly - and that can have all kinds of non preferred consequences.

The stern sections on the Chincogan 52 are quite flat in cross section. This helps to dampen pitching and probably helps with a little lift when reaching in the higher speed range.

THE MAIN PARAMETERS

A fat hull will have high form drag. A hull too skinny will have higher drag from skin friction. We want asymmetric water planes and a reasonably flat rocker to minimise pitching. A fine entry will minimise slamming in short steep waves and throw less spray. A flat run aft in cross section will promote planing or semi planing at speed. A straight run aft with a shallow release angle in the rocker line will also help to improve performance downwind in fresh air.

A rocker line that is too flat will be slow to tack and will suffer in the light from increased wetted area.

Changing any one of these parameters affects at least one other, and most likely most of the others. It's the mix of all of these factors that determines all round performance and seakeeping

behavior.

Moving the rig well aft might be a good idea for high speed reaching in waves, especially if the boat is light. Move it too far aft in a cruising boat and you have problems providing enough buoyancy in the aft sections without creating a lot of drag.

Same problem if you try to flatten the rocker too much and neglect the fundamentals of hull volume and location of the centre of buoyancy. If you sink the transoms you're digging holes and you're you're not getting a clean wake.

Planing power boats and dinghies benefit from flat rocker and a broad transom. It's a combination of the flat underbody and heap of power that makes them work.

For sailing catamarans, and cruising cats in particular there are other factors to take into account and if the transoms are digging holes in the low and medium speed range you are compromising all round performance.

Digging holes is hard work. It's not fun and it's not fast.

The profile of Chincogan 52 Cat'chus. You can make out the bustle in the rocker concentrated where the anode is at the point where the drive shaft exts the hull. The draft at this point provides us with the buoyancy we need to carry the weight aft but also allows for a flat rocker line aft and a clean exit at the transom. I should note that the Chincogan 52 is light for its length (Cat'chus was around 8.6 tonnes at launch). A light displacement allows us to keep reasonably shallow draft and flat rocker in the design stage.

This is Carbon Copy, the same boat that went on to win a host of major racing titles under three different owners as Mad Max, Ullman Sails, and currently Team Fugazi. As evidenced in the photos here Carbon Copy has adequate designed displacement to keep the leeward transom clear even while flying a hull.

Her hull lines are published in an article titled "What Makes Max Fast"

DEALING WITH WEIGHT DISTRIBUTION

Catamarans typically carry a lot of weight aft with engines, davits, solar panels, dinghies, and people in the cockpit all contributing to the need for buoyancy aft. So the dilemma for the designer is how to support this weight without creating a fat transom or an excessively rounded rocker line?

Turning back to racing boats for clues we can point to a highly successful series of sports cats that carry a distinctive hull form. The cats I'm referring to are my own designs.

Silveraider, Mad Max, Indian Chief, Flat Chat, and several others that have performed consistently in racing in Australian waters over more than three decades. Between them these cats have claimed titles on handicap and on elapsed time in every major race or racing series held in Australian waters over that period.

All of these boats share the same family of hull shapes. They don't have flat rocker lines, they don't bury the transoms at rest and they don't carry their rigs aft of the 50% position.

The rocker line in these boats is gently curved coming aft to about 70% to 75% aft of the bow, then it has a subtle but distinctive kick or bustle where it carries the maximum buoyancy before running aft to the transom quite straight and shallow in profile, allowing the flow to exit cleanly. It's not something I invented, its a hull form in use by designers around the world and it was in play on Lock Crowther's designs (notably the Shockwave 40) long before I discovered it.

The effectiveness of this hull shape is ideal for cruising cats as well as racing boats and we have been using it on a wide range of designs including the new Raku series of cats.

Left: Chincogan 52 Soul trims with her transoms well clear even though in this shot she is fully loaded for long term cruising.

Below: Cut Loose took the concept of "long and skinny" with a modest platform to the next level. A 55'er with the accommodation of your average 40'er

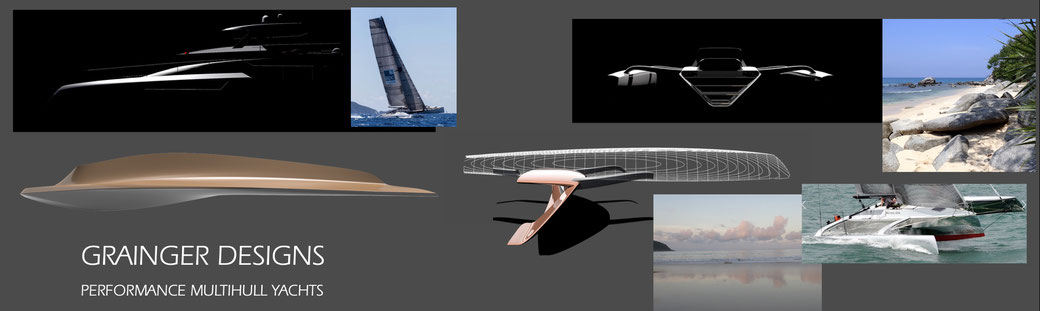

Keep up with fresh ideas and inspired design from Grainger Designs. We won't bug you with a barrage of emails. Maximum of two per month.