PART 4. MAKING MAGIC with Beauty

4.1 On Beauty in Design

4.2 Resolved Design

4.3 Beauty sends a message

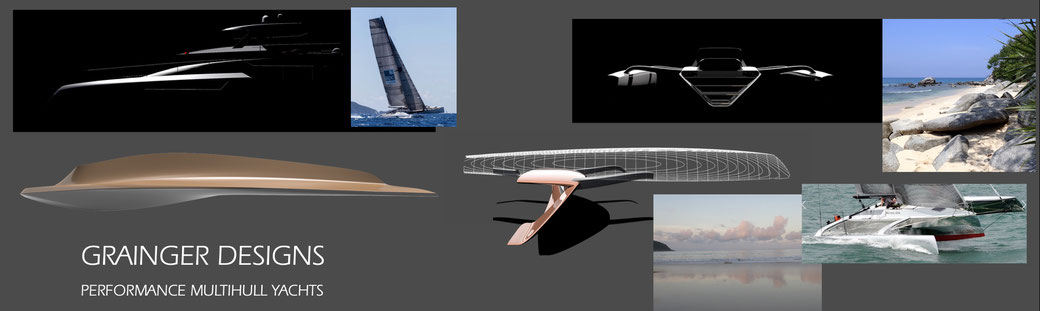

4.4 Beauty in Product Design

4.5 Beauty in Maths and Physics

4.6 Beauty in Complexity

4.7 Beauty in Simplicity

4.8 That intrinsic unfathomable Quality

4.9 The Creative Edge

4.10 Summary

4.1 On Beauty in Design

There's a dimension to design that is deeper than just an effective assemblage of features that fulfil a prescribed purpose. It's one step beyond the utility of the product or service in question and it dwells in a dimension that defies rational analysis. Its' flaws are undeniable, ever present but they're tolerated, even cherished. It's a dimension that speaks of art, of poetry, harmony, beauty.

It's a dimension than can spring forth in a moment of inspiration, a moment that bursts forth for the designer after years of relentless searching, failed experimentation, and possibly a period of deep reflection, even despair at not easily finding the path to resolution.

Creativity often happens when we are not thinking hard about a problem, when one's mental focus is diffuse.

Creativity often arrives on inventing new analogies which allow us to see an old problem in the light of new comparisons and combinations of ideas.

All too often the design project is considered to be finished when all of the features of the design have been incorporated but without due consideration for how efficiently or how elegantly the various features have been incorporated. Such ill considered designs can be regarded as assemblages of features on one hand and a lost opportunity on the other.

4.2 Cohesion and Harmony in Design - Resolved Design

A visually harmonious object prompts in us a feeling of a harmonious life; Plato

When you can sense in a product or a piece of art that the creator had a clear purpose or vision in mind, and had managed to execute that vision in a way that truly reflects the intent of the designer, possibly in a very subconscious manner, the product makes a statement that appears both natural and effortless. In a product that is for practical purposes only, a toaster for example, the effort of the designer might never be noticed by the user of the product, in which case the designer has successfully fulfilled Dieter Rams' fifth law of good design, that good design is unobtrusive.

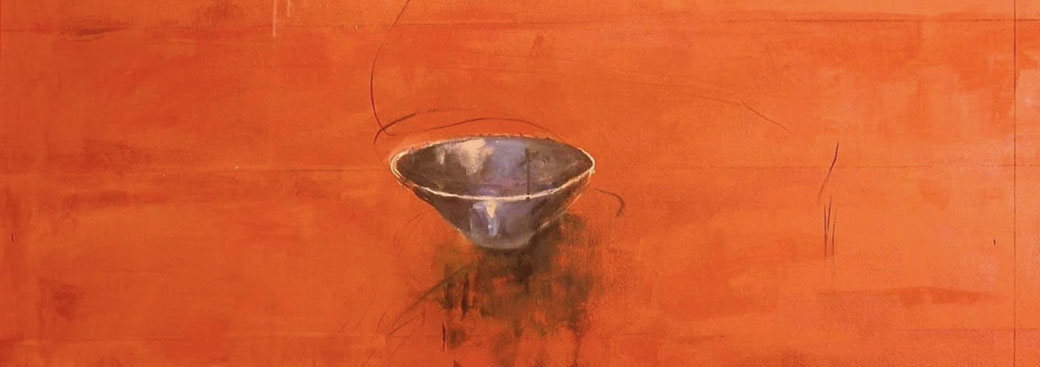

We can apply the same argument to art - that it should both reflect and illuminate the artist's intent. But art is different in that it is not useful in a utilitarian sense, and so the emotional reaction it produces is more fundamental. Design can be good art, and art can be built on good design, but the success of art is far more dependant on the emotional response from an aesthetic stance.

What we can say that art and design have in common is that the work seeks to be resolved, a term used a lot in the art world to describe a work that is not overworked, would not be improved if more detail was added, and where all of the elements of the work are united in creating the desired emotional reaction.

We don't hear the word resolved used so much in the design world and there's really no good replacement for it in the English language. We can try with adjectives like unified and cohesive. Some other cultures are better at describing the effect, especially Eastern and South East Asian Languages.

Good Design is integrated design. The product is a cohesive package that doesn't have awkward spots because something had to be pushed or pulled out of shape to fit in. Nothing is finished until the whole is resolved. A resolved design is what most designers aspire to achieve but all too often the initial vision for the design gets hijacked by the need for features, for profit, or for preconceived ideas of the patron who cares little for the notion of a resolved design.

And all too often we see designs that are an assemblage of design features driven by the notion that more features will create a better product.

4.3 Beauty Sends a Message

We wonder over its purpose. Is beauty subjective or objective?

Beauty is deeply connected to our experience of the world.

It can emerge unexpected from a diverse range of sources.

It can be observed in the natural world it can be created though human endeavour in the arts, science, in mathematics and in the wondrous order of the universe.

Much more than a matter of aesthetics or superficial appearance, beauty is deeply connected to the way we create meaning and enriches our lives. It enables us to us see and appreciate the world in new and exciting ways.

In the world of business and in the arts beauty can be a key factor in creating products, services. t is an essential element of successful marketing and communication. Beauty has the potential to inspire and engage audiences, and to create meaningful experiences that make a positive impact on the world.

Beauty can be a difficult concept to define. It can be subjective, elusive. The pursuit of beauty requires a willingness to take risks, experiment, and explore new ideas. It is ultimately about creating work that connects with people on a deep and meaningful level.

Beauty has the power to communicate ideas and emotions in a direct and powerful way.

Beauty may be dismissed in contemporary culture as superficial or trivial, but it can play a vital role in connecting with audiences on a deep emotional level.

To create a beautiful product is to signal that the creator cares about the product and the consumer's engagement with the product, reaching to quality of manufacture, durability, usability and purposefulness. To create a beautiful product is to signal that it's about a lot more than the profit margin.

4.4 Beauty in Product Design

Dieter Rams' Third Principle of Good design states "Good Design is Aesthetic"

The aesthetic quality of a product is integral to its usefulness because products we use every day affect our person and our well-being. But only well-executed objects can be beautiful.

Beauty affects our mood, our appreciation of the world around us. We want to live in beautiful places, or at least visit beautiful places. We want to be surrounded by beautiful things in our lives.

Designer Stefan Sagmeister goes straight to the point:

99% of ugly things that exist in the world have not been made by someone who wanted to make them ugly, they’ve been made by somebody who didn’t give a shit.

Robert Brunner-Director of Industrial Design for Apple Computer from 1989 to 1996 and a founder of the Ammunition Design Group writes;

As a car lover, I have always felt the 1963 Porsche 911 platform was an amazing, radical design that has stood the test of time. It lives today as an evolved, yet familiar form with direct lineage to the original. Every iteration is based off of that original configuration, and it remains classic and modern all at once.

I have my own Porsche 911 story. In my mid teens I went to the snow fields with my family and for the first time saw not one, but two spanking new Porsche 911's side by side in the car park, and was immediately transfixed. I remember asking my father; "It must cost about the same to build a beautiful car as a mediocre looking car or even an ugly car. So why don't all car companies build beautiful cars?"

Of course the argument is a lot more nuanced than that - but beauty turns heads, it creates a lasting impression and gives products a sense of desirability, a level of appreciation that people are willing to reach deeper into their pockets to pay for.

Superficially the Porsche 911 was little more than a refined Volkswagen Beetle, but here was some intrinsic quality embedded in the design of those 911's that was able to communicate the designers' intent.

Where's the sex? When Steve Jobs summed it up succinctly when he returned to Apple in 1997 to take the CEO role back from Gil Amelio

Jobs invited the top level employees to a conference where he asked;

"What's wrong with his place"? and after a pause announced "It's the products!"

So what's wrong with the products? … and after another pause announced "The products suck!"

"There's no sex in them anymore."

Jobs put Apple back on track with Design - both visual and functional and the company has gone on to become one of the most successful ever on planet earth.

My first computer was an Apple Mac and so has been every computer I've owned since. In the early days of Apple there were times when I was frustrated that the most advanced design and engineering software was only available on Intel based computers, and they were just so goddamn ugly I could not bring myself to have one on my desk. At the time I was sure that someone would eventually recognise the opportunity to hire a designer with a little bit of talent and a vision, and design a computer that would challenge Apple's dominance in the field of good looking electronics hardware. To the best of my knowledge some 40 years later this still hasn't happened.

Products need to be more than reliably functional to be successful. They need to imbue character. They need to inspire by illuminating the designer's purpose and passion behind their work.

The Shakers have a proverb that says, "Do not make something unless it is both necessary and useful; but if it is both, do not hesitate to make it beautiful." Kevin Kelly from What Technology Wants

We believe that design's primary job is to be useful and beauty may or may not be integrated into the process of design. If it is left until last there's a risk it's going to be superficial. When beauty is embedded in design as part of the process it appears natural, unforced.

For some, for design to be successful in its usefulness is success enough. But As Kevin Kelly says; "No matter how rational our thinking, we hear a voice whisper that beauty has an important role to plav." "To incorporate that intrinsic quality of beauty is to add value that helps to make design memorable."

Do people care?

In 1998 Ford Australia brought to market the AU Falcon sedan. The styling, which Ford labelled "New Edge" was kind of soft and squishy even for its time, but in particular it featured a rather droopy rear quarter which was way out of line with the popular consensus among designers (and a significant portion of the public) that cars should feature powerful haunches reminiscent of a large animal poised to pursue their prey.

The design program for the AU Falcon had cost AUD700 million over 4 years and the styling did polarise the car buying public to some extent. However Ford still managed to sell nearly 240,000 units of the AU Falcon before the model was discontinued in 2002.

4.5 Beauty in Maths and Physics

Beauty in Maths and Physics

Beauty in mathematics can refer to the aesthetic appeal of certain mathematical concepts, equations, and structures, which can be appreciated for their elegance, simplicity, symmetry, and clarity.

Many mathematicians find beauty in the elegance and precision of mathematical proofs, the elegance of mathematical formulae, and the aesthetic qualities of geometric shapes and patterns. Beauty in mathematics can also refer to the deep insights and revelations that mathematical discoveries can provide about the universe and the human mind.

Beauty in mathematics is a concept that has been explored by many mathematicians and philosophers throughout history. Mathematics is often considered a beautiful subject, and many mathematicians describe their work in terms of beauty or elegance.

In mathematics, beauty can be seen in the simplicity and elegance of a solution or proof, as well as in the patterns and structures that are in his book "Unweaving the Rainbow,"

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins discusses the beauty of science and the natural world, arguing that a scientific understanding of the universe can enhance, rather than diminish its wonder and beauty.

Dawkins writes;

The feeling of awed wonder that science can give us is one of the highest experiences of which the human psyche is capable," and that scientific explanations can reveal the underlying elegance and simplicity of the natural world.

Joscha Bach, a cognitive scientist and AI researcher, has discussed beauty in various contexts, including its relationship to creativity, complexity, and computational aesthetics. He has written that beauty is a measure of how well we can compress information and that creative systems tend to be good at finding regularities and patterns that are pleasing to the eye or ear.

Joscha Bach has also explored the concept of "aesthetic induction," which posits that we derive a sense of beauty from experiencing things that conform to the patterns and regularities of our environment. According to Bach, the brain has an innate sense of what is aesthetically pleasing, and it can be trained to recognise and appreciate new patterns and structures through exposure and experience.

Moreover, in his work on AGI (Artificial General Intelligence), Joscha Back has noted that developing AGI that is capable of creating truly beautiful and aesthetic artifacts requires a deep understanding of what makes things beautiful to humans, which he believes is a broadly cultural and historical concept that varies across different societies and periods of time.

Roger Penrose, a mathematical physicist and Nobel laureate, has written about beauty in mathematics, physics, and the natural world. He sees beauty in the elegance, symmetry, and simplicity of mathematical models and theories, and has argued that a scientific understanding of the universe can reveal deep and profound beauty. In his book "The Emperor's New Mind", Penrose writes that "a discovery of great beauty in mathematics is one where the truth can be perceived fairly directly, with little in the way of computation or subtlety."

Penrose has also discussed the beauty of physical laws and theories, noting that they often possess a kind of aesthetic appeal and elegance, despite their complexity. He has argued that certain mathematical or geometrical concepts, such as the golden ratio or the Penrose tiling, have an intrinsic beauty that goes beyond their function or utility.

Furthermore, Penrose has expressed wonder and awe at the beauty and mysteries of the universe, such as the weirdness of quantum mechanics, the complexity of biological organisms, and the elegance of the laws of physics. He has written that the universe seems to be remarkable precisely because it is so incomprehensible and that beauty lies in discovering these mysteries and delving deeper into the fundamental nature of reality.

Eric Weinstein is a mathematician and economist who has spoken about the concept of beauty in the context of science and mathematics. He believes that beauty is a fundamental aspect of scientific inquiry and discovery, and that it is closely tied to the pursuit of truth and knowledge.

Weinstein argues that beautiful scientific ideas and theories are those that are simultaneously elegant, simple, and powerful. He believes that the pursuit of beautiful ideas is essential for advancing scientific knowledge and achieving breakthrough discoveries.

According to Weinstein, the pursuit of beauty in science requires a willingness to think creatively and unconventionally. He suggests that the most beautiful scientific ideas often emerge from nonlinear, intuitive modes of thinking, rather than from rigid adherence to established theories and paradigms.

Overall, Weinstein's perspective on beauty emphasizes its potential to inspire and guide scientific inquiry, and to create new insights and understandings of the world around us. He believes that the pursuit of beauty is an essential component of both scientific creativity and the human quest for knowledge and understanding.

Daniel Schmachtenberger is a social philosopher who has spoken about the concept of beauty in the context of human culture and civilization. He believes that beauty is a critical aspect of creating a thriving society, and that it is closely connected to other important human values such as meaning, purpose, and wellbeing. Schmactenberger argues that a beautiful society is one that is founded on principles of justice, sustainability, and ethical responsibility. He believes that a truly beautiful civilisation must prioritise the welfare of all its members, rather than focusing exclusively on the interests of a privileged few.

According to Schmachtenberger, the pursuit of beauty in society requires a deep commitment to ethical and moral values, as well as a willingness to work towards real-world solutions to complex problems such as poverty, climate change, and social injustice. He believes that the creation of a beautiful society is a collective responsibility, and that it requires the active participation of all individuals and communities.

Overall, Schmactenberger's perspective on beauty emphasises its potential to inspire and guide human values and actions in the pursuit of a more just and equitable world. He believes that a truly beautiful society is one that is both ethically responsible and deeply meaningful, and that it has the power to transform human consciousness and experience on a global scale.

Theoretical physicist Lee Smolin argues that scientific theories should be evaluated not only by their empirical success but by their aesthetic qualities and the elegance of the concepts and principles they employ. Smolin expresses the view that beauty plays a central role in scientific discovery and the development of scientific theories.

In his book "The Trouble with Physics," Smolin writes about the beauty of physics and the importance of aesthetic criteria in the process of scientific discovery. He argues that scientific theories should not only account for known phenomena but also be open to criticism and revision, and that beautiful theories tend to be more durable and have greater explanatory power than those that lack elegance and simplicity.

Smolin has also explored the concept of "cosmic natural selection," which suggests that the universe may evolve through a kind of evolutionary process in which successful physical laws, or "genes," are passed down through generations of universes. He sees beauty as playing a crucial role in this process, with the most beautiful and elegant laws being the ones that are most likely to be successful and passed on to future universes.

"Most evolved things are beautiful and the most beautiful are the most highly evolved". Kevin Kelly

Beauty in Philosophy

Plato puts forth the idea that we are drawn to beauty because it signals the perfect ideal we aspire to attain. A visually symmetrical object alludes to a feeling of fairness and equality. The philosopher wrote mainly of art and nature, but this is also true of product design. It is shortsighted to say that people like beautiful products simply because they like to look at nice things.

Going deeper, it is more accurate to state that people like beautiful products because they align with the feeling of progress they want to make towards a perfect ideal.

Beauty is not an add-on—it is an accurate expression of its utility. A beautiful product needs its purpose to be tightly intertwined with its visual expression. But, more often than not, a product’s purpose is hindered by its ugliness.

Plato theorized that humans constantly seek an idealised perfect version of something and that beauty is a measurement of the vector towards that end.

… the beauty of a mathematical formula or model lies in its ability to provide a concise and elegant description of complex phenomena.

Stephen Wolfram

Euler's Identity; commonly referred to as the most beautiful equation

Beauty in Philosophy

Plato believed that beauty was an abstract universal concept that belonged to the realm of Forms or Ideas. For him, the physical world was merely a reflection or copy of the perfect and eternal Forms, and beauty was one of the most important of these Forms.

According to Plato, the beauty of physical objects was not simply a matter of subjective opinion, but rather reflected their participation in the eternal and objective reality of the Forms. He argued that our sensory experience of beautiful things in the world was only a glimpse of the perfect and eternal beauty of the Form of Beauty itself.

Plato also believed that the pursuit of beauty was an essential part of a fulfilling life. He argued that by contemplating the Forms, including the Form of Beauty, humans could achieve a deeper understanding of reality and attain a state of wisdom and inner harmony. For Plato, the pursuit of the transcendent beauty of the Forms was one of the highest goals of human life.

Plato puts forth the idea that we are drawn to beauty because it signals the perfect ideal we aspire to attain. A visually symmetrical object alludes to a feeling of fairness and equality. The philosopher wrote mainly of art and nature, but this is also true of product design. It is shortsighted to say that people like beautiful products simply because they like to look at nice things. Going deeper, it is more accurate to state that people like beautiful products because they align with the feeling of progress they want to make towards a perfect ideal.

Beauty is not an add-on—it is an accurate expression of its utility. A beautiful product needs its purpose to be tightly intertwined with its visual expression. But, more often than not, a product’s purpose is hindered by its ugliness.

Plato theorized that humans constantly seek an idealised perfect version of something and that beauty is a measurement of the vector towards that end.

Every year of my life I am less convinced that there is anything subjective about beauty. Beauty is something that scientists tend to agree on to use as a pointer in the direction of truth.

David Gelernter - Philosopher and Mathematician

Plato believed that beauty was an abstract universal concept that belonged to the realm of Forms or Ideas. For him, the physical world was merely a reflection or copy of the perfect and eternal Forms, and beauty was one of the most important of these Forms.

According to Plato, the beauty of physical objects was not simply a matter of subjective opinion, but rather reflected their participation in the eternal and objective reality of the Forms. He argued that our sensory experience of beautiful things in the world was only a glimpse of the perfect and eternal beauty of the Form of Beauty itself.

Plato also believed that the pursuit of beauty was an essential part of a fulfilling life. He argued that by contemplating the Forms, including the Form of Beauty, humans could achieve a deeper understanding of reality and attain a state of wisdom and inner harmony. For Plato, the pursuit of the transcendent beauty of the Forms was one of the highest goals of human life.

Plato believed that beauty was an abstract universal concept that belonged to the realm of Forms or Ideas. For him, the physical world was merely a reflection or copy of the perfect and eternal Forms, and beauty was one of the most important of these Forms.

According to Plato, the beauty of physical objects was not simply a matter of subjective opinion, but rather reflected their participation in the eternal and objective reality of the Forms. He argued that our sensory experience of beautiful things in the world was only a glimpse of the perfect and eternal beauty of the Form of Beauty itself.

Plato also believed that the pursuit of beauty was an essential part of a fulfilling life. He argued that by contemplating the Forms, including the Form of Beauty, humans could achieve a deeper understanding of reality and attain a state of wisdom and inner harmony. For Plato, the pursuit of the transcendent beauty of the Forms was one of the highest goals of human life.

Aristotle believed that beauty was an objective characteristic of the world that could be understood through empirical inquiry. He proposed that beauty was not simply a matter of individual taste or preference, but rather was grounded in the structure of reality itself.

According to Aristotle, beauty was a feature of things that exhibited a harmonious proportion and symmetry, and that were pleasing to the senses. He argued that our experience of beauty was rooted in our natural human capacities to perceive order, harmony, and balance, and that it was an important aspect of our enjoyment of life.

Aristotle also believed that the pursuit of beauty was intimately connected to the pursuit of excellence and virtue. He argued that the cultivation of aesthetic taste and appreciation of beauty was a key component of a virtuous and fulfilling life. For Aristotle, the pursuit of beauty was not something separate from the pursuit of the other goods in life, but was rather an integral part of achieving a state of eudaimonia, or human flourishing.

4.6 Beauty in Complexity

Beauty can be found in complexity but it's not to be confused with complexity which can be disguising disorder and incompleteness.

Stephen Wolfram, a British physicist, mathematician, and computer scientist, has discussed the concept of beauty in his work in several ways. He has argued that the universe and the systems it contains exhibit a kind of inherent beauty that can be revealed through scientific exploration and computation.

In his book "A New Kind of Science" Wolfram writes "simple programs can produce great complexity, often of remarkable regularity and beauty." He has also suggested that the beauty of a mathematical formula or model lies in its ability to provide a concise and elegant description of complex phenomena.

Furthermore, Wolfram has developed a concept called "computational irreducibility" which suggests that some systems are inherently complex and cannot be simplified or predicted. Instead, the only way to understand their behaviour is to simulate them. This concept challenges the traditional notion of beauty as something that is simple and elegant. Wolfram has argued that the inherent complexity found in these systems can itself be considered beautiful because of the richness and diversity that emerges from it.

Ian McGilchrist is a writer, psychiatrist, and philosopher who has spoken about the concept of beauty in the context of human consciousness and culture. He believes that beauty is an essential aspect of human experience, and that it is deeply connected to our sense of meaning and purpose in life.

According to McGilchrist, beauty is not just a matter of aesthetics or sensory experience, but is rather a holistic and multi-dimensional experience that engages our emotions, our intellect, and our sense of value. He argues that beauty is closely tied to our sense of connectedness to the world and to each other, and that it has the power to inspire and transform us on a deep and profound level.

McGilchrist also emphasises the importance of embracing complexity and ambiguity in the pursuit of beauty. He believes that the most beautiful experiences and works of art are those that challenge our understanding and force us to confront the contradictions and paradoxes of the world around us.

Overall, McGilchrist's perspective on beauty emphasises its potential to create meaning, connection, and understanding in our lives, and to help us navigate the complex and multidimensional world around us. He believes that the pursuit of beauty is an essential aspect of human consciousness and culture, and that it has the power to transform us on a fundamental level.

4.7 Beauty in Simplicity

Profound simplicity is inherently much more challenging to design well than complexity.

To simplify a product, the designer must understand which elements are essential and how they can be combined, excluding the superfluous, in a way that enhances the user experience while maximising performance.

It is extremely satisfying to come full circle and be able to present a product that is simple not through elimination but through integration.

Dario Valenza

When we admire a simple situation for its good qualities it doesn't mean we wish we were back in the same situation. The dream of innocence is of little comfort to us; our problem, the problem of organising form under complex constraints is new and all our own. But in their own way the simple cultures do their simple job better than we do ours. I believe that only careful examination of their success can give us the insight we need to solve the problems of complexity.

Christopher Alexander

When you work as a researcher, you have to enlarge your knowledge, include all the possible information. But when you act as a designer, you have to totally change the approach, you have to be selective, exclude possibilities and arrive to one unique physical configuration.

Architect Stefano Boeri

"When you're forced to be simple, you're forced to face the real problem. When you can't deliver ornament, you have to deliver substance."

Paul Graham

When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty. I only think about how to solve the problem. But when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.

Richard Buckminster Fuller

Co-founder of Sony Corporation Akio Morita commissioned his engineers to design the walkman specifically so he could he listen to an opera in its entirety on a flight from Tokyo to LA.

When they brought him the prototype they had added record functionality. Mortia objected - he hadn’t asked for it. The engineers insisted that the device could record with only a very small increase in the cost. Morita insisted the record function be removed. He wanted the customer to be able to understand clearly what the device was for and be able to make a decision to purchase on that basis alone.

One of the great dilemmas for an artist; many would say the greatest dilemma, is knowing what to leave out, when to stop, at what stage is the next brush stroke going to be fatal to the success of the work. On flipping though some long neglected sketch books I came across this quick note I had scribbled on one of the pages;

"How do you know what to leave out, and where does it go when you don't include it?"

Brian Eno recounts in an interview with the BBC's Spencer Kelly that when he first started working on tape his tendency was always to put more stuff in. The work was often improved when the producer suggested to leave some things out and see how it sounds, often resulting in a significant improvement to the work.

I really enjoyed this story from US based writer and business strategist Matthew E. May.

"Normally I have more ideas than I know what to do with. Several years ago, however, I ran out of them".

"At the time, I was working closely with the senior leadership of a very large and successful Japanese company. I had been hired to help it develop new ideas and strategies in the United States, but was struggling with a particularly difficult project that required me to reconcile two completely different perspectives. Eastern and Western ways of thinking are often at odds with each other. I found myself at a standstill."

"I must not have done a very good job of hiding how useless I was feeling, because a 2,500-year-old snippet of Chinese philosophy found its way to me anonymously, via a handwritten note on a Post-it stuck to my work space."

“To attain knowledge, add things every day. To attain wisdom, subtract things every day,” it said, capsulising teachings of Lao Tzu. “Profit comes from what is there, usefulness from what is not there.”

My first thought was, “Someone wants me gone — I’d be more useful that way.”

But as I read it again and thought about it, lightning struck.

It dawned on me that I’d been looking at my problem in the wrong way. As is natural and intuitive, I had been looking at what to do, rather than what not to do.

But as I read it again and thought about it, lightning struck.

It dawned on me that I’d been looking at my problem in the wrong way. As is natural and intuitive, I had been looking at what to do, rather than what not to do. But as soon as I shifted my perspective, I was able to complete the project successfully."

Good design is as little design as possible

Less, but better — because it concentrates on the essential aspects, and the products are not burdened with non-essentials.

Dieter Rams

Rams was talking about designing things you can see and feel. But we’re entering a new era, one in which designers create experiences centring not on physical objects but on the fabric of digital information that surrounds us. That’s the next great challenge for design: weaving the threads of technology, information, and access seamlessly and elegantly into our everyday lives. When a social network automatically checks us into a location, or cashiers can suggest new products based on our purchase history, or our connected TV calls up our favourite shows when we walk into the living room (all things that are either happening now or coming soon), it may seem like magic. But these are carefully designed experiences. They just follow Rams’ dictum—they appear invisible.

Lightness in Design

If you're working on the design of a road embankment, a battle tank or a bulldozer you may skip over this section, but there's a certain joy in design that expresses lightness that intersects with our appreciation of simplicity and elegance.

The auxiliary technology has to be light enough and efficient enough that it doesn’t degrade the performance of the primary technology.

Cars that have petroleum and electric are being supplanted by all electric. This will happen to marine vessels that have diesel and electric (and sails).

It’s like baking a cake or making a piece of art. Get the right ingredients in the right proportions and you have a masterpiece. Get it wrong and you have a mess.

Wu Wei in Design

Wu Wei is a Chinese term that comes from Taoist philosophy and is often translated as "effortless action" or "non-doing." It refers to a state of being in which one acts in harmony with the natural flow of life, rather than trying to control or manipulate events.

In Taoism, the concept of Wu Wei is considered central to living a fulfilling and harmonious life. The idea is that when one acts in accordance with the natural way of things, life becomes easier and more fulfilling. On the other hand, when one tries to control events and impose one's will on the world, life becomes more difficult and less satisfying.

Wu Wei does not mean complete inaction or passivity. Instead, it refers to taking action in a natural and spontaneous way, without forcing or imposing one's will. It is a way of living in which one allows events to unfold as they will, while still taking action in line with one's goals and values.In this sense, Wu Wei can be seen as a form of mindfulness or presence in which one is fully engaged in the moment.

Scientists, mathematicians and engineers search for theories that explain highly complex phenomena in stunningly simple ways. Musicians and composers use pauses in the music — silence — to create dramatic tension. Athletes and dancers search for maximum impact with minimal effort. Filmmakers, novelists and songwriters strive to tell simple stories that foster both multiple meanings and universal resonance.

"The principle of subtraction carries over to the corporate world. Here are some examples: W. L. Gore, recognised as one of the world’s most innovative companies, eliminated job titles in order to release employees’ creativity. When it started out, Scion, the youth-oriented unit of Toyota, decided not to advertise, and it reduced the number of standard features on its vehicles to allow buyers to customise their cars. The British bank First Direct operates successfully without branches, relying instead on Internet, telephone and mobile transactions. Steve Jobs revolutionised the world’s concept of a cellphone by removing the physical keyboard from the iPhone. Instagram, acquired last year by Facebook, grew quickly once its first version, called Burbn, was stripped of many of its features and reworked to focus on one thing: photos.

The lesson I’ve learned from my pursuit of less is powerful in its simplicity: when you remove just the right things in just the right way, something good happens".

About Matthew E. May

Matthew E. May is the author of “The Laws of Subtraction: 6 Simple Rules for Winning in the Age of Excess Everything.”

You can also find it on TED X

"Even though the idea of subtracting things every day was thousands of years old, it was still radical to me. I decided to explore the idea further. I discovered an essay by the management educator Jim Collins, in which he confirmed the ancient philosophy: “A great piece of art is composed not just of what is in the final piece, but equally important, what is not. It is the discipline to discard what does not fit — to cut out what might have already cost days or even years of effort — that distinguishes the truly exceptional artist and marks the ideal piece of work, be it a symphony, a novel, a painting, a company or, most important of all, a life.”

"In reading several articles in scientific literature, I discovered that subtraction lights up a brain scan differently than addition does, because it uses different circuitry. In fact, accident victims suffering brain injuries often lose their ability to both add and subtract, retaining only one of the two. Subtraction is literally a different way of thinking.

While it hadn’t occurred to me to use subtraction in my own job, I realised that it is at the root of many professions".

Jason Silva is a filmmaker and futurist who has spoken extensively on the subject of beauty. He believes that beauty is a universal human need that is essential for our well-being and survival.

Silva argues that beauty is closely tied to our sense of wonder and awe, and that it has the power to inspire and transform us. He believes that beauty can open our minds to new possibilities, and help us to see the world in new and profound ways.

According to Silva, the pursuit of beauty is an essential component of human creativity and expression. He believes that art, music, and other forms of creative expression are vehicles for exploring and communicating the beauty of the world around us.

Silva also emphasizes the importance of embracing vulnerability and imperfection in the pursuit of beauty. He believes that true beauty is often found in the unexpected and the unpredictable, and that our willingness to take risks and push boundaries is the key to creating work that is truly beautiful and transformative.

Overall, Silva's approach to beauty emphasises its potential to inspire, challenge, and transform us, and to create a more vibrant and fulfilling human experience.

Wagener's preoccupation with meeting the expectations of new buyers has, understandably, impacted on interior design, too. Although on-trend, he isn't keen on touchscreens in cars. He waves his iPhone and says "I'm a fan of the touchpad when it's in my pocket, but not when you're driving. But what I do like about the iPhone is that it shows that reduction is the key. Complexity has increased by 10 times in the last five years, so when we draw a line, we take it away, we reduce the shapes to their minimum. That's what my philosophy is all about."

General Principle: the solutions (on balance) need to be simpler than the problems.

Otherwise the system collapses under its complexity.

Frank Chimero it would seem is strongly influenced by Wu Wei . In his extended essay The Shape of Design he writes;

" I believe projects have character. Problems have a natural grain, just like materials. The grain suggests the best way to treat the problem, much like how the grain of wood can show you how to cut, bend, or fasten it. Go with the grain and your work improves by using natural affordances; go against the grain and you undermine the integrity of your construction by weakening its materials. It takes time for the problems' grain to unfold, but once it starts to show itself, the articulate designer can begin describing what they sense. With this new focus, the design process becomes an attempt to make the work ever more definite, nuanced, and clear"

4.8 That unfathomable Intrinsic Quality

Robert M. Pirsig, in his book "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance" argues that quality is not just an objective measure, but a subjective and holistic experience that involves both the rational and the intuitive. He describes quality as the underlying reality and ultimate goal of human endeavour, and suggests that it can be understood through a process of uncovering or revealing rather than creating it. Pirsig suggests that the pursuit and attainment of quality is a key factor in achieving a fulfilling life.

Quality isn't a method. It's a goal towards which method is aimed.

We can define quality as a measure of how well something performs its intended function, and how well it satisfies the needs and desires of its users including the elements of durability, reliability, functionality, aesthetics, customer service, and overall satisfaction.

But for most of us this definition leaves us cold and wanting to dig deeper. There is something mysterious that we call quality that is inherent in some objects, in some actions, in some works of art. We intuitively know it's in there but difficult to identify, to point to.

We can try to make it obvious with glossy packaging and advertising, higher prices and endorsements by people of high public profile - and this kind of trickery can be effective as long as the proposition is broadly accepted.

I would suggest that quality is something you sense, and you sense it because it has been injected into something by a force that is difficult to trace.

We may say we know quality when we see it, but all too often it's missing from our gaze because our glance is superficial or we haven’t put in the time and effort to appreciate the writing of a great author, the thinking behind the work of a great artist or the finesse and craftsmanship behind a precision piece of equipment.

For the ancient Greeks there was no distinction between art and the discipline of making things. The word techne was used to encompass the skills and techniques of weaving, pottery and metalworking and over time came to encompass all forms of practical knowledge and expertise including medicine, philosophy and rhetoric.

In the 17th century, the term "technology" began to be used in English to refer to the practical application of scientific knowledge, particularly in the fields of manufacturing and industry. Since then, the meaning of the term has continued to evolve, and today it generally refers to the tools, techniques, and processes used to create, design and improve products and services across a wide range of industries and fields.

As our technologies have evolved, so too, have our perception of the products we produce and part of this is the perception that a certain level of beauty, of quality, has been diluted or in some cases completely lost.

To paraphrase Pirsig; The real ugliness lies in the relationship between the people who produce the technology and the things they produce. This results in a similar relationship between the people who use the technology and the things they use"

Pirsig goes on to argue that "at the moment of pure quality subject and object are identical …it is this identity that is the basis of craftsmanship in all the technical arts. And it is this identity that modern dualistically conceived technology lacks.

This wall is beautiful because the people who worked on it had a way of looking at things that made them do it right unselfconsciously. They didn't separate themselves from the work in such a away as to do it wrong. There is the centre of the whole solution.

Seth Godin, a marketing expert and author, has written extensively about the importance of quality in business and creativity. He argues that quality is not just a matter of meeting certain specifications or standards, but is rather a subjective and evolving concept that is deeply connected to the needs and desires of customers.

According to Godin, the key to achieving quality in creative endeavours is to focus relentlessly on serving the needs of the audience or the market. He believes that true innovation and excellence come from understanding the desires and aspirations of the people you are trying to reach, and from creating work that connects with them on a deep and meaningful level.

Overall, Godin's approach to quality emphasises the importance of customer-centric thinking, risk-taking, and continuous improvement in achieving both business success and creative excellence.

The ancient Greek philosophers on Quality

Plato and Aristotle both had important insights on the concept of quality.

Aristotle recognised the importance of qualities like beauty, goodness, and truth in human life, and he believed that they were objective features of the world that could be studied and understood through empirical inquiry. He proposed that qualities were inherent in the objects themselves, and that they could be observed and studied by examining their characteristics, functions, and relationships to other things.

Plato believed that qualities were inherent in the objects themselves, and could be observed and studied through empirical inquiry and careful observation, that.the ultimate reality of the universe was the realm of abstract forms, or ideas, which provided the perfect and eternal standards of qualities like beauty and goodness.

Both Plato and Aristotle recognised the importance of qualities like beauty, goodness, and truth in human life, and they believed that understanding and pursuing these qualities was essential for achieving a fulfilling and meaningful life.

Quality is both reflection and projection. We reflect on quality in appreciating the object of our attention. And we project quality when we express that appreciation in our words, our writing, or in the things we produce. Our thoughts produce a garden of ideas in our subconscious, maybe even a jungle. They lie there dormant until such time as we’re motivated to activate them or to eventually discard them in frustration as the work appears futile and unproductive.

And then only to retrieve them at a later date, render them and maybe by chance produce something that makes the whole effort worthwhile.

Quality and beauty. They inhabit the same spaces, they mingle and merge, they play and jostle for attention. Sometimes easy to put in one bucket or the other, sometimes not.

A bare metal structure might be considered beautiful in form. another of the same form with a protective coating might be considered to be of superior quality until the bare rusting metal of the unprotected form takes on a patina that might at once express both beauty and a certain "quality".

A timber plank washed up on the shore might have potential quality as material for making something, it might lose that quality over time but attain a certain beauty in the process of weathering and decay.

The vocabulary we have at hand to express such concepts is not always precise when employed to convey the emotions that arise from our observation of the world around us.

Creative ideas don’t appear from nowhere. The attention we pay to the world around us seeds our creative memories, and the closer the attention we pay the healthier and more prolific are those seeds.

We may say we know it when we see it, but all too often it's missing from our view only because our glance is superficial. We haven’t put in the time and effort to appreciate the writing of a great author, the thinking behind the work of a great artist or the finesse and craftsmanship behind a precision piece of furniture or equipment.

Quality is both reflection and projection. We reflect on quality in appreciating xxxxxxxxxxx

And we project quality when we express that appreciation in our words, our writing, our art or the manufactured things we produce.

Our thoughts produce a garden of ideas in our subconscious, maybe even a jungle. They lie there dormant until such time as we’re motivated to activate them.

We draw them back to the surface, prune them and reorganise them into new combinations, eventually to discard them in frustration as the work appears futile and unproductive. Then only to retrieve fragments of them at a later date, reorder them and maybe by chance create something the makes the whole effort worthwhile. This is the dance we dance between creativity and entropy.

The Lines of a Master Draughtsman

At was a late afternoon in high season when the bay is typically graced with maybe fifty or sixty boats on anchor. I was out for a late afternoon SUP paddle among the vessels resting on anchor in the calm of the bay. Somehow my attention was firmly drawn to one particular monohull and I felt compelled to paddle to it and ask the owner the nature of its origin.

It's an Irens he told me. I was both surprised and impressed that the vessel that had attracted my interest so strongly had come from the pen of one of my most admired designers, a designer whose work was largely instrumental in firing my own ambition to become involved in design. What made it all the more remarkable was that I had not been aware of any history of Nigel Irens working in the field of monohull sail boats.

At the time I had no idea what magic Nigel had woven to make the lines of this boat so special, and I still don't, but my curiosity was now at rest in the simple knowing that this particular vessel had been created by someone with a deep and natural sense for good design. The lingering question was what magic was it in the draughtsman's work that had produced something that was in one sense modest… and yet so "right".

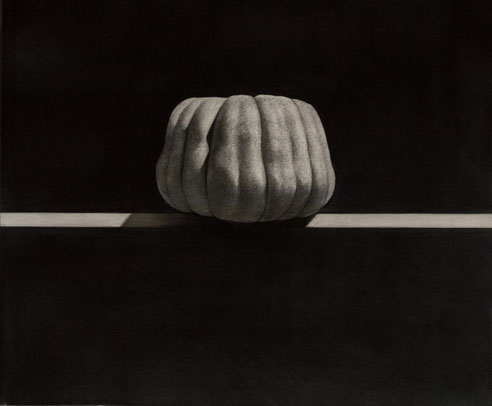

This is a pumpkin. You can pick one up at your local produce market for a couple of dollars. Or if you don't like pumpkin that much you can just take a photo with your cell phone for a cost of virtually nothing.

So why would you go to the Olsen Gallery and offer somewhere between 300,000 and 400,000 Australian dollars for a picture of a pumpkin? You can't eat it and it's not even in full colour.

This pumpkin in this image was rendered in charcoal by the renown Australian artist William Delafield Cook who died in London in 2015 while preparing for an exhibition. Cook was world renown for his realist art which included incredibly detailed paintings of otherwise ordinary hills, trees, cabbages and haystacks. Things that we normally don't make the effort to take a second glance.

What the artist was able to do was render an object or a scene in such a way that we see it differently. The image evokes a realisation and draws an emotional response. We sense that passion the artist invested in the work and if we buy the work we're buying a little bit of that passion for ourselves. Skilled designers and craftsmen do the same thing. Feeling can be embedded in design. They create a product that speaks of a passion, or maybe just a humble dedication to their work.

We define ourselves by the by the things we choose to posses and surround ourselves with. Successful design cements the connection we make with those objects.

The price we pay for an exceptional work of art or a finely crafted everyday product is more than pure indulgence. It's more than showing off. It's a measure of our appreciation for the time and effort that a craftsman, a designer, or a manufacturer has put into their creativity.

Beauty summary

Beauty Summary

Beautiful design communicates clearly and effectively, it resonates with people on a deep and meaningful level.

Beauty is an essential element of design, and that it has the power to create a sense of connectedness and meaning in our lives.

It is not just a matter of aesthetics or visual appeal, but is rather a holistic and multi-sensory experience that engages our emotions, our intellect, and our sense of value.

The subjective/objective dichotomy is ever present in the beauty debate, but while the subjective view of beauty is difficult to rationalise there is a wealth of evidence and logical argument to support the notion that beauty is inherent and objective whether or not the beauty is noticed or appreciated.

…if you could be creative by applying ordinary logic, then anyone who was logical could do it, and the fact is they can’t. There are some extraordinarily logical people who actually are not terribly good at being creative. Creativity comes from the unconscious, that’s where most of the really unusual and special ideas come from. …

John Cleese

Design can be messy, we can waste a lot of time going back and forth without a clear direction, putting up ideas that are too difficult to build, too expensive and totally unworkable in the real world.

But experimentation and free thinking can also lead to breakthrough technologies, freshly inspired styling and new solutions to age old problems.

Writer, Designer Frank Chimero encourages us to consider the three levers of design and to creatively adjust those levers to create new work with meaning and value.

The levers are the message, the tone, and the format

All design work seems to have three common traits: there is a message to the work, the tone of that message, and the format that the work takes. Successful design has all three elements working in co-dependence to achieve a whole greater than the sum of the individual parts.

The tone is the expressed in the way the elements of the message are combined. The tone is made up of such things as style.

The format is the artifact and related directly to the why.

Any creative pursuit is like solving an endless puzzle. You don’t know where to start because there are no edges. So, you start with the two things in front of you that fit together, and then build on it. And no edges means no obvious stopping point. Any time you step back to look at what you’ve done, it’s an intermediate step. When you’re “done” is a completely arbitrary choice. Creativity is a quagmire.

Frank Chimera

There was a time when most districts of most cities had a cohesive nature to their building style. Some buildings beautiful, some not so much, but a sense of time and place prevailed in the architecture. It still exists to a large extent in many cities but usually in older industrial areas that have not seen too much development. These would seem to be under constant threat from the “look at me” nature of a lot of contemporary architecture.

The disruptive nature of contemporary architecture in our cities is a sign of the unordered transition from traditional building methods to the more technologically advanced architectural methodologies where structures jostle for attention and often don’t sit comfortably beside their counterparts.

Although in design we are hard-wired to consider beauty to be a basic and superficial quality when creating something, maybe we should acknowledge how important it may be. Beauty in the things we design and produce matters. Yes, design needs to be smart, and yes, it needs to be functional. But at the heart of it all, give beauty the time and care it deserves. Make it enjoyable to look at, the rest will follow.

As Stefan Sagmeister says, “Beauty is at the heart of function,” and thus, “beauty is human.”

Keep up with fresh ideas and inspired design from Grainger Designs. We won't bug you with a barrage of emails. Maximum of two per month.