Part 2. How design gets done

What has changed during our lifetime is the pace of innovation. So technological development now outpaces our ability to adapt to it, which has caused a flare in our anxiety about technology and its impact. So this anxiety comes from technology outpacing our ability to understand it. And I think there's some reality to this. Obi Felten

Solving Complexity with Process

Design is not a Process, it’s an Odyssey. It is not a rigid structure with steps to follow, but a path you discover along the way with dangers, villains, and wisdom to be gained, and you often wind up right back where you started.

Ryan Ford

AGE OF THE HYPER OBJECT

if you're a designer, all of this stuff is coming into your world now and increasingly over time.

It's going to get a lot messier. We're basically entering an era and an age of the hyperobject.

Our modern world runs on massively connected systems living amongst constructs that lie beyond the scope of what we as humans can grasp and hold in our minds at any given point in time. Design needs to find new tactics to deal with these ever increasing levels of complexity.

Processes for Progress in Problem Solving

Various structures and frameworks have been developed to deal with problem solving in design, including Design Thinking, Double Diamond, Vision Thinking and the more analytical approach taken by Mathematician and Architect Christopher Alexander.

Does the work of designing complex systems call on formal processes for successful outcomes?

There are two basic principles for approaching these complexities.

The first is to develop a working process that allows for exploration of possible solutions and means to assess progress.

The second is to break the problem down into a list of sub assemblies. As technology evolves faster and faster the intuitive resolution of contemporary design problems lies beyond the grasp of a single designer. Solutions are found by disassembling systems in order to present them as a series of smaller problems that can be rearranged for optimum efficiency and allocated to specialists.

Process 1. Design Thinking

Process 1 Design Thinking

“Design thinking is a human-centred approach to innovation that draws from the designer's toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.” Tim Brown, president and CEO IDEO

REORIENT TO PROJECT-BASED WORK RATHER THAN PROCESS-BASED WORK

"Wherever one can shift people from a process mentality to a project mentality can make a huge difference whether those projects are large or small," Tim Brown

Design thinking is not a methodology that can be universally applied to all design projects but it is another way of creating a framework for building creative ideas to solve problems. It creates a structured process that is repeatable and can be applied across a range of disciplines including entrepreneurship, design and management. It pairs the rational and the creative in the interest of a productive work environment and a better outcome for the product or service. It creates an environment that fosters right brain creativity functioning cohesively with left brain analysis.

Design projects sometimes take place in an environment where designers have little understanding of business practice which is often regimented and inflexible, and business leaders have little understanding of the creative process. This situation encourages the potential for conflict and unsatisfactory outcome for the product or service. Design Thinking is a way of integrating the design process with management and business leadership in a cohesive way that promotes cohesive working relationships a successful outcome.

In any large project intent on bringing a new product or service to market there are two skill sets; strategy and design. Design Thinking is about integrating these skills, not separating them.

Process 2. Double Diamond

Process 2.

Double Diamond is the name of a design process model popularised by the British Design Council in 2005,[1] and adapted from the divergence-convergence model proposed in 1996 by Hungarian-American linguist Bela Banathy.

The Double Diamond is graphically represented by two diamond shapes starting with the initial challenge or problem statement to the left, moving through a definition of the problem to be addressed in the centre and ending with the solution to the right. The diamond shapes represent how divergent and convergent thinking fit within each stage. Symbols in each phase represent points of iteration for research, learning, prototyping and testing.

The simplicity in the symmetry of the diagram helps with the introduction of the concept and its subsequent application.

Increasing complexity and interdependence calls for greater specialisation and greater organisational skills.

Regardless of how much discovery and problem-solving design teams execute in the Double Diamond — or any other design process — their effort becomes meaningless when the scope is futile and lacks purpose. Double Diamond is a structure that breaks the design process into four phases:

Discover - The process starts by questioning the challenge and quickly leads to research to identify user needs.

Define - The second phase is to make sense of the findings, understanding how user needs and the problem align. The result is to create a design brief which clearly defines the challenge based on these insights.

Develop - The third phase concentrates on developing, testing and refining multiple potential solutions.

Deliver - The final phase involves selecting a single solution that works and preparing it for launch. Designer and writer Ryan Ford, while a strong advocate of the Double Diamond process has some reservations; in particular that the process lacks vision. To quote from one of his essays;

"…after many years of practising the process, I have concluded that perhaps it’s missing a crucial element — a vision". I would argue that while the vision is essential it not a part of the structured process, it is the spark that ignites the process and should permeate the process at every turn.

Regardless of a team’s design process, they should always start with a clear vision. Doing so stimulates creative thinking about the bigger picture, which includes value-driven outcomes, not just a single technology solution or a futile feature-factory idea.

The missing element of the Double Diamond design process Design teams need more than just a process; they need a clear understanding of why they do what they do.

Process 3 Vision Thinking

The Double Diamond with a cherry on top.

Adding vision-thinking as a new phase (or diamond) to the Double Diamond is like adding a cherry on top of a multi-layered cake. It provides design teams with a necessary starting point before they begin tucking into the various layers.

Kickstarting the design process with a vision diamond also stimulates holistic thinking and fosters confidence and certainty throughout the proceeding stages. Design teams understand the broader picture that involves making the right impact on people.

The vision diamond contains two essential parts:

Understand: Ideas for the purpose, cause, or belief

Define: A vision that everyone can acknowledge and pursue

1) Understand: diverge to explore ideas for a vision

Design teams work alongside the organisation’s business layer in the first step to understanding the overarching purpose. They adopt holistic thinking to generate ideas on contributions that lead to desired people and business-related outcomes.

2) Define: converge to define the vision

In the subsequent step, design teams with the business layer translate broad ideas into a simple vision statement. The definition should reflect the desired, positive contributions and outcomes. Furthermore, everyone is clear on working toward agreed goals and value-driven outcomes.

Once realising the vision, design teams can confidently embark on their journey to creating good products for the right cause. However, if teams find themselves conflicting with or steering away from their purpose, they must revisit the vision diamond to recalibrate their compass.

Is Structure a Crutch?

Design Process and the danger of over confidence in working with structure.

Busting out and breaking the rules are at the heart of modern jazz.

Great jazz musicians improvise but you don't become a great jazz musician without first learning the rules and studying the structures that are at the heart of a great piece of music.

I think we can look at the process of design in the same light. With enough practice the work will evolve less effortlessly. Whatever process is employed the results come more easily through the subconscious.

Too Much Information

"When a designer does not understand a problem clearly enough to find the order it calls for he falls back on some arbitrarily chosen formal order. The problem, because of its complexity, remains unsolved".

Christopher Alexander - Notes on the Synthesis of Form.

Alexander makes the point that in most design situations there is way more informations to be organised and integrated than any one single person can deal with at any given time. Our modern technologies incorporate increasingly higher levels of interacting systems and processes that are becoming too complex to grasp intuitively.

Typically such complexity is dealt with piecemeal as the task of integrating various aspects of the design bring deeper complexities to the surface. It's an effect that mathematician and philosopher David Berlinski refers to as combinatorial inflation.

On Flow

The ultimate reason why these methods of Design Process, Design Thinking, and Design Doing have been so over-defined is rooted in a need to help legitimise design amongst other functions, departments, and domains within companies.

Design so often sits at the intersection of Business Goals and Customer Impact, and so it has a need to provide others with a sense that it knows exactly what it’s doing, it has predictable output, and it can meet deadlines. All of this influences those who fundamentally do not understand Design.

René Bieder, Art Director, Graphic Artist and Font Designer writes;

It took me a while to get a feel for spacing and proportions. I was working on Gentona and training my eyes by looking at traditional sans serifs, and I had a surprising insight: Uniformity doesn’t occur through using patterns but by getting a feel for proportions. That is something you cannot learn by reading a book. You have to do it over and over again. That may sound obvious, but in comparison to my previous grid-based strategy, where most of the elements have a rational explanation, I had to train my eyes to see how to get the proportions right in order to achieve an overall balanced look. Sometimes the smallest detail totally changes the appearance of the entire font. This was something I knew from logo design but applying that to a glyph set of 400+ characters was tough learning.

Ultimately working with a structured process is a way of reducing the gap between a designer's capacity to solve complex problems and the daunting task of resolving a multiple of variables into cohesive and satisfying solution.

There is no guarantee that the outcome of such a structured process is going to look right or function flawlessly however rigorously the rules and guidelines have been followed. But the process serves as a structure to build ideas and enhance the possibility of finding better solutions with a minimum of energy.

Design Process 4. Getting the Idea - Solving complexity with Subdivision

Robert M Pirsig in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance views the motorcycle as an idea that can be divided by its components and according to its functions. He places components and functions each in their respective boxes at the head of the hierarchy of subdivisions. Motorcycle components get divided into the power assembly and the running assembly, and these in turn get divided into finer and finer sub assemblies that eventually combine to form a structure, in this case a motor cycle.

Pirsig considers his own view of the motorcycle to be a rational intellectual "idea" that is fundamental. By way of contrast his friend John, according to Pirsig, looks at the motorcycle and sees steel in various shapes. Same motorcycle. Two contrasting ideas.

We can take any structure, be it a physical object or a problem to be solved and break it down into sub assemblies, smaller components that allow us to carefully examine the effectiveness of each component in turn. However this way of working exposes the risk that in the process of optimising individual components, their role as a cohesive functioning component of the idea becomes compromised. This presents the problem that by dealing with the detail of any one classification on its own we are at risk of creating solutions that are not a good fit on the whole, the big idea.

We can create a list of requirements for solving any design problem. It might take into consideration the concerns of the manufacturer, (availability of materials, ease of assembly), the concerns of the customer (durability, price, aesthetics), and the concerns of third parties such as environmental authorities and public safety experts.

Architect and writer Christopher Alexander argues that since we are not able to refer to the full list every time we set out to solve a problem we invent a shorthand for the problem by breaking down the elements of the problem into distinct classes.

Alexander contends that the designer never really understands the context fully. He may know piecemeal what the context demands of the form but he does not see the context as a single pattern - a unitary field of forces.

Alexander puts forward the argument that in our advanced culture there is no structural correspondence between the problem and the means at hand for solving it. The complexity of the problem is never fully disentangled and the forms that are produced lack a formal clarity that they would have if the organisation of the problem they are fitted to was better understood.

Alexander sets out to address this lack of understanding by proposing a structured method for analysing design problems. In his book Notes on the Synthesis of Form (1964). He proposes that solutions be sought through the realisation of constructive diagrams in an effort to understand the required form so fully that there is no longer a rift between its functional specification and the shape it takes.

Alexander creates diagrams (that he later refers to as patterns) of physical relationships which resolve a small system of interacting and conflicting forces and is independent of all other forces and all other possible diagrams. The idea is to create abstract relationships one at a time and to create designs which are whole by fusing these relationships.

According to Alexander a good designer invents form that will "penetrate the problem so deeply that it not only solves it but illuminates it".

Alexander's overview of the "the idea" finds substantial agreement with that of Pirsig. That is; each writer is concerned with the nature of complexity and the importance of fit within the context of the idea. The difference lies in the way Pirsig's rather philosophical approach sits in contrast to Alexander's rather structured, mathematical diagnosis of the problem. The two views are not in conflict. On the contrary each has its own field of emphasis and is complimentary in aiding our ability to analyse and solve complex problems.

And so when working on resolving design problems it's the question that seeds the idea. The idea and all of its sub components must remain firmly in view throughout the process of resolving the design.

SOLUTION ENTROPY

Ryan Ford writes on Medium;

But I want to introduce a term that we've been using a little bit, which is solution entropy. Which is this notion that we never really solve anything.

We might break down a big problem into smaller problems, or we might even kick the problem down the road a bit, or kick it into different companies, or help reduce it down into smaller parts. But it never really goes away. This is a term that we've used a little bit. I'd like you to use a lot. But I think it really helps you get out of that mindset of thinking, somebody set me a task.

I learned design as a problem-solving exercise, like a plumber or something. Most people just use the first line, which is, "When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck.

There were no shipwrecks in a world before the ship was invented." And I think we have to start addressing the fact that when we think we're solving something, what we're actually doing is breaking down a bigger problem into smaller problems, or punting it somewhere else.

So when you invent USB-C, you invent dongles. USB-C is undoubtedly a good protocol, a useful connector. But you also then have to deal with all of the other things. The problem is not solved. It's changed.

Form and Context

A constantly evolving relationship at the heart of good design

“There’s the whole Buddhist thing about the essence of a bowl being its emptiness—that’s why it’s useful. Its emptiness allows it to hold something. I guess that means that design must talk about something else. If you make design about design, you’re just stacking bowls, and that’s not what bowls are for.”

Frank Chimera

A lot has been written about the relationship between form and context. Not so much about context itself

Context determines the functionality we require from what we are are creating. Form is the shape and organisation we create to fit the context. In many design situations it is relatively easy to create form that satisfies the context. But the success of the design relies on having the context clearly in mind when we start to create the form and in finding a solution that finds a harmonious fit with the context.

Form

For a bowl the requirement might be to hold fruit and so the form is rudimentary. If the bowl is to be decorative then the context is modified.

The context for a boat hull might be to accommodate a given number of passengers and crew, to handle specific sea conditions or to be propelled at a certain speed by a given form energy. If the form is required to incorporate all three requirements then the process of resolving the design can become very complex and will almost certainly involve an extended exercise of adjusting the relationship between the three requirements. It may also necessitate adjusting the relationship between form and context.

Where form and context are in conflict more work is required to try to resolve the design. In this case creativity is in high demand. Where there is harmony between form and context the outcome is likely to come more easily and the the final outcome to be more pleasing. If the solution is complex and the struggle to resolve the design shows in the final solution the product will be less satisfying.

This is what Dieter Rams is referring to in his fifth principle of good design when he says "good design is unobtrusive".

For the boat, depending on size and complexity there is probably more than enough context scenarios to fill a book.

In the process of design the critical issue is not to make sure the context is covered in its entirety because a lot of it is intuitive. If contemporary design practice is followed a lot of the context takes care of itself without any great effort on the part of the designer.

We know intuitively the engine and the tanks will fit in the hull without having to spend a lot time investigating that. The design exercise of fitting the engine and the tanks is relatively effortless and doesn't require any significant modification to the hull.

On the other hand a raised flybridge on a sailing boats affects weight, windage, sail efficiency, the requirements of more deck space for access, and the overall aesthetic. This is a complex design exercise that requires compromise in many areas.

The crux of the problem with boats.

If you need a pick up truck to carry your tools or tow your day boat, but you love high performance driving, and you only want one car you have a choice to make. You can buy the sports car or the pickup truck. There not a lot of product to choose from where you'll get full satisfaction with a compromise.

With boats it's a bit different. You can have that compromise. But you have to understand that it's a compromise. And in many cases that compromise is not understood clearly.

The Indonesian Paraw and the Thai Long Tail are built on land adjacent to the beach, sometimes even right on the beach. There are no plans. There is no school that teaches boat building. There are no specifications, no inspectors to examine the structure to ensure it complies with a particular set of rules.. But there is knowledge and there is understanding.

Style as an element of form.

A very plain car can be said to be devoid of style. Or maybe we can say that "its' style is obvious in its' avoidance of it."

Lamborghini oozes style - maybe a little too much some might say. For each the context is similar; a road transportation vehicle. But not the same. One might inspire you to find a deserted stretch of road with broad sweeping curves, the other might leave you devoid of any inspiration at all. The Lamborghini has the potential to become a sports vehicle and this is a case of form modifying context.

Context gives rise to form and form can modify context in a cycle of constant adjustment.

When style and form are in harmony with the idea design is enhanced.

TRADITIONAL DESIGN AND MODERN DESIGN

In the process of problem solving, and that's what design is, its problem solving, I find myself returning time and time again to the writings of Robert M Pirsig, of Kevin Kelly, of Christopher Alexander, but especially Alexander.

Alexander uses the terms unselfconscious design, and self conscious design to differentiate between the architectural creations of cultures that build with traditional methods, as opposed to the more technically advanced cultures that employ specialisation and complex, ever evolving technologies in their creative output.

Where Alexander uses the terms unselfconscious design, and self conscious design I prefer to use the terms traditional and modern to differentiate these two genres, with the disclaimer that advanced does not necessarily mean better, but infers a higher level of specialisation and almost always means greater complexity. Another term that could have replaced self conscious in Alexander's writing is "evolved". Because that's exactly what he's referring to. He's comparing long standing cultures who resist change, or simply don't see a need for it' - with modern cultures who are heavily preoccupied with innovation and technological advancement. Evolution does occur but only in the sense of modifying tools and structures where whey are found to be deficient, whereas the more advanced cultures are intent on "creating the new" often in disregard to whether it might be an improvement on what exists now.

In traditional cultures form making is resistant to change and relies on patterns of learning that have evolved slowly over time. The only incentive to change being circumstances where corrections or modifications are required to deal with a predicament of one kind or another.

In modern cultures tradition and religious belief have little influence and change for its own sake becomes acceptable. The need for equilibrium is replaced by a quest for improvement and reinvention.

The Cost Benefit Equation

The cost benefit equation

A glossy fibreglass boat on display at the boat show on a sunny afternoon displays large windows- a spacious cabin structure, beamy hulls for ample accommodation below decks and some lovely recessed sun beds up forward in the bows.

The cost benefit of this vessel on display at the boat show or at rest in a sheltered bay might be very attractive. In another context, say a 40 knot gale with rising head seas, the appeal of this design might be diminished when compared to a vessel with fine hulls, streamlined superstructure with less wind resistance and decks designed to quickly shed water coming on board.

This is a graphic example of how ideal form is changed in different contexts.

In the first context, the protected enclosure of the boat show, the form can be easily defined, as it can also be relatively easily defined for the context of the boat in a 40 knot gale.

We can create any number of cost benefit studies for the boat. Some of these might include accommodation facilities, fuel efficiency, ease of use, maintenance requirements, sea keeping abilities. Each of these is a context against which the design can be measured, and where the cost benefit analysis will produce a different valuation

Finding a compromise that suits the context of multiple conditions is more complex and requires an understanding of the requirements of both conditions if a successful outcome is to be arrived at.

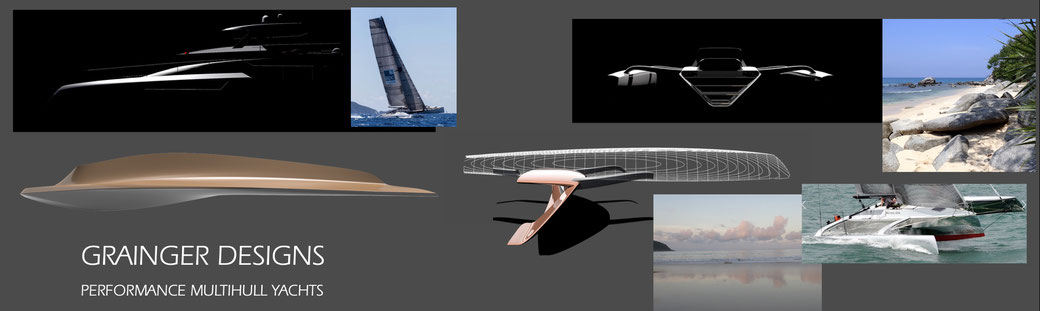

Keep up with fresh ideas and inspired design from Grainger Designs. We won't bug you with a barrage of emails. Maximum of two per month.